The Pareto principle (also known as the 80/20 rule) specifies an unequal relationship between inputs and outputs by stating that, for many phenomena, 20% of invested input is responsible for 80% of the results obtained.

This principle is named after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto who, in 1896, published his first paper “Cours d’économie politique” where he essentially showed the unequal distribution of wealth among the population in Italy: approximately 80% of the land was owned only by 20% of its inhabitants.

Although the original observation was in connection with population and wealth, generally speaking the Pareto Principle is the observation that most things in life are not distributed evenly. It can mean all of the following things:

- 20% of the input creates 80% of the result

- 20% of the workers produce 80% of the result

- 20% of the customers create 80% of the revenue

- 20% of the bugs cause 80% of the crashes

- 20% of clothes in a wardrobe are worn 80% of the time

- And on and on…

However there is a common misconception that the numbers 20 and 80 must add to 100. They actually don’t! 20% of the workers could create 10% of the result. Or 50%. Or 80%. Or even 100%.

Clearly most things in life (effort, reward, output) are not distributed evenly and definitely some contribute more than others.

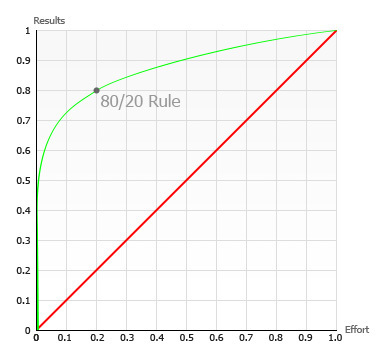

Out of 100 experiments/projects/candidates perhaps only 1 will be “cool”. That cool idea/product/person will result in majority of the impact (the green line of the graph below). We’d like life to be like the red line, where every piece contributes equally, but that doesn’t always happen:

Why is this useful to know from a HR and Managerial perspective?

In a perfect world, every employee would contribute the same amount, every bug would be equally important, every feature would be equally loved by users and planning would be easy but unfortunately this is not the case. The rule helps us realizing that the majority of results come from a minority of inputs. Knowing this, if:

20% of workers contribute 80% of results- We must focus on rewarding and retaining these employees.

20% of customers contribute 80% of revenue- We must focus on satisfying these customers and keep strong relationship with them

20% of bugs contribute 80% of crashes: Focus on fixing these bugs first.

The examples go on. The point is to realize that you can often focus your effort on the 20% that makes a difference, instead of the 80% that doesn’t add much.

This is surely one of the simplest and most powerful management tools on the planet and its potential use can cover most aspects of work, business, organizational development and personal life.

In economics terms, there is diminishing marginal benefit. This is related to the law of diminishing returns: we more often are spending lots of time on the minor details.

The value of the Pareto Principle for managers and leaders is that it reminds them where to really focus on. Of the things you do and work during your day, only 20 percent really matter. Those 20 percent produce 80 percent of your results. Identify and focus on those things. If something in the schedule has to slip or if something isn’t going to get done, make sure it’s not part of that 20 percent.

Same theory applies to people management: managers should focus their limited time on managing only the superstars. In reality managers spend a large portion of their time on employees that demonstrate performance or behavior issues.

All of us, HR and Management, should spend more time on acknowledging the major contributions of the excellently performing “vital few.” Recognition programs, rewards, access to additional diverse responsibilities can motivate this positive vital few to perform even better and to encourage other team members to improve their own work habits.

What can occur is similar to the spreading of a “positive performance” antibody in the work place. The vital few can become the “vital many” with that kind of encouragement.

There is another use perhaps for the “vital few” idea, one which probably even Pareto did not consider. That is the role of an employee’s family/friends/hobbies in the employees’ personal life. More and more the desire and request of a work-life balance reflect the need of spending more time than we now do nurturing our relationships with our family and friends, cultivating our hobbies and spend time more wisely.

For the employer, this also means ensuring that the benefit program is flexible and responsive to life stage changes that affect all of us. Our benefit needs are different when we have young children than when we don’t, or when we are single or approaching retirement.